Conservation agencies and volunteers are out in jack pine forests in parts of the U.S. and Canada, searching for and counting a particular kind of bird, the Kirtland’s warbler.

At 5:45 a.m. I met up with a couple of Michigan Department of Natural Resources experts at a GPS coordinate, because one of the roads at the rural intersection was unnamed.

“We are in middle Kalkaska County at one of our Kirtland’s warbler management areas and we are about to go and count some birds,” said Erin Victory, the Northern Lower Peninsula Ecologist Planner for the Wildlife Division of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources and the Kirtland’s warbler coordinator.

Along with us for the count at this site was Keith Kintigh, assistant chief of DNR’s Wildlife Division.

The Kirtland’s warbler nearly went extinct until there was an effort to restore its habitat.

This census used to be held every year, then every other year as the bird’s population increased. Now the census is done every fourth year. That’s because the population in the U.S. and Canada has gone from a low of 167 singing males in the 1980s to about 2,000, according to the last census.

The team usually doubles that number to include the females in the total population of the bird. They don’t usually see the birds. They count by listening for those males.

“This census is unique in conservation in that we attempt to count an entire population. That just doesn’t happen in most cases. We attempt to estimate population size. But with the Kirtland’s warbler census we are trying to find every singing male that exists,” said Kintigh.

With dawn breaking, the birds started singing. We were lucky because we didn’t have to struggle to go through the thicket of the young jack pines. There’s a sandy two-track road that goes around the area to be surveyed.

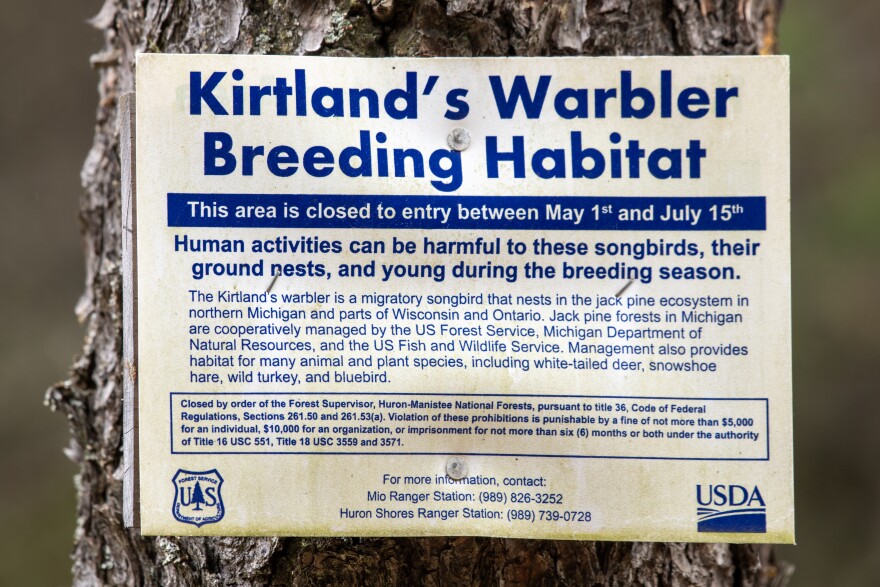

Jack pines are key to the Kirtland’s warbler’s existence. They will only nest in young jack pines that still have branches low to the ground.

“They’re ground nesters so that lower branching is really beneficial to protect the nest and the young,” said Victory.

Insects on those lower branches are more accessible.

As the trees grow and get older, you don’t get those lower branches that protect the nests anymore.

“And that’s about the time that they move out,” Victory said.

New, younger forests have to be planted on public lands because the natural phenomenon that used to result in more frequent new growth was fire, usually caused by lightning.

Jack pines typically need fire to reproduce. It causes the wax-covered pine cones to open. Then, new trees sprout up so close together that it’s hard to walk through. Burning down forests is not so popular these days since that pine forest can be turned into lumber.

The DNR rotates the harvest and planting of these jack pine forests so that there are always enough young jack pines for the Kirtland’s warblers.

The site we’re surveying is a little different than other jack pine plantation sites.

“A lot of the planted trees died because of drought. That reduced the density of trees, but then we also had some natural regeneration of jack pine here which is sort of unusual. It doesn’t always happen without fire, but it can happen sometimes. And that happened here. So, it led to this being a really unique site,” Kintigh explained.

So how do you count birds, when often you can only hear them? It is methodical. The counters walk 200 meters, stop, listen for five minutes, and with a compass, they plot where the birds are so they don’t double-count. Victory and Kintigh work together to confirm what they find.

This kind of scene is happening in many sites across Michigan, as well as Wisconsin and Ontario. The Kirtland’s Warbler Alliance coordinates many volunteers, working with the Michigan DNR and the U.S. Forest Service to conduct the census.

For the Kirtland’s warbler males, the struggle to find a mate is real. One bird was belting out his call, but Kintigh noticed another bird nearby was only doing half the call at half the volume.

“This guy is probably getting his butt kicked by this guy over here that’s been singing. So, he’s being real careful. He’s like whispering, ‘Hello ladies. Anybody here?’”

We circled the jack pine forest 200 meters at a time and then it was time to see if Keith Kintigh’s prediction at the beginning of the count was correct.

Lester: "So, Erin, Keith said we’d see — or hear — maybe one warbler today. How did that turn out?"

Erin: "He was wrong. (laughing) We saw 18 times that many."

Lester: "Were you surprised, Keith?"

Keith: "I was pleasantly surprised, yes. I hadn’t been to this site in probably eight or nine years and in my mind, it had aged further along than what it was. So, it was great. It was a great morning.”

Saving the Kirtland’s warbler from extinction is a significant success story. The bird was taken off the federal endangered species list in 2019. But Erin Victory noted that it won’t continue to recover without help, and it's still on the state threatened species list.

“The species is what we call a ‘conservation reliant species,’ which means that it will continue to need management in order to persist on the landscape. And so, the work that we do here is essential for the species to continue to be part of Michigan’s natural heritage.”

Just a side note: Michigan’s state bird is the American robin. Two other states also claim the robin. Audubon magazine suggested that Michigan should make the Kirtland’s warbler its state bird and also should consider renaming the bird the Jack Pine Warbler. Discuss.